Ditte Goard: Flotsam and Jetsam Workshops 2014

The Shelter project has developed around ideas of autonomy and collaboration, and involves a questioning of ownership, leadership and authority. The shelter acts as an open, anonymous space, belonging to no one and yet belonging to everyone who encounters it, a space to be curious, to experience on your own terms, to take from it as much as you put in. So, given that it is possible for art and artists to succeed in encouraging open and autonomous engagement, then the conversation could extend beyond the art world – not least to the troubled sphere of education, which is an activity that could in principle operate in a similar way but in practice rarely does.

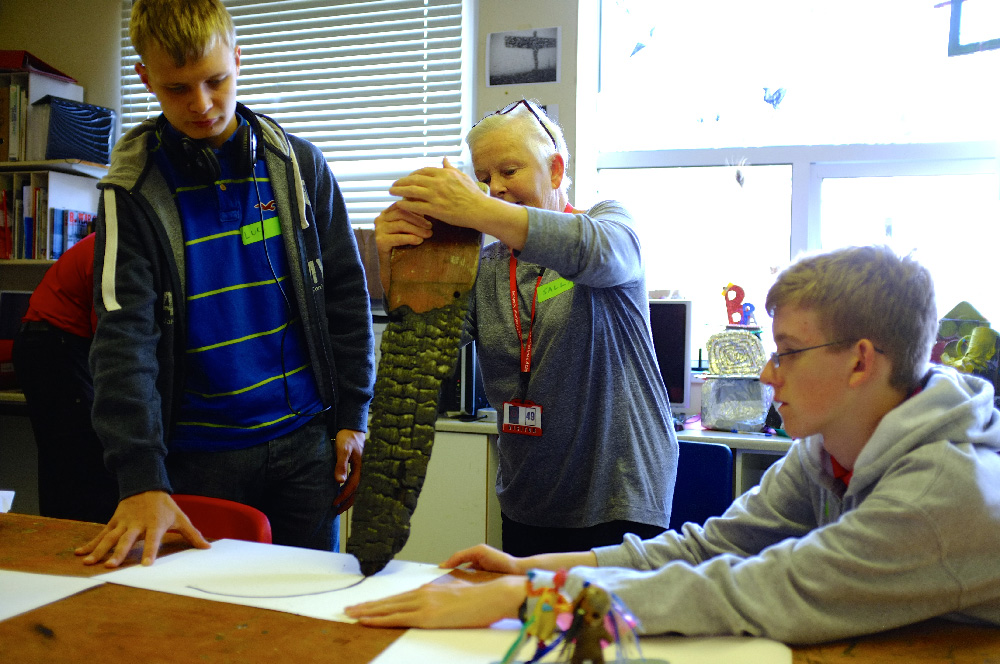

As part of my 6-month work experience with the Shelter project, I took part in organizing and delivering workshops in two schools around the theme of ‘Flotsam and Jetsam’. During June 2014, Sally and I arrived at each school armed with several boxes full of Holy Island’s finest flotsam and jetsam. After the beach-combing event previously that month, we wanted to facilitate workshops that used discarded objects as a basis for making and discussing art. The schools we visited each had very specific characteristics. The first, the Barbara Priestman Academy in Sunderland, provides designated education for students with ASD (Autistic Spectrum Disorder) and/or complex learning difficulties. The second, Lowick First School, which combines with Holy Island School when the tide allows safe crossing, has a maximum of 33 students who learn together in one open-plan classroom. Neither school is what one might call ‘standard’, yet they have established what most ‘standard’ schools actually aspire to: a creative and engaging educational experience crafted around the needs of individual learners.

At Barbara Priestman we worked with seven students who, under the guidance of art teacher Dave Fudge, have developed an open and critical view of art and its potential. We began by showing the students work by a number of artists who use discarded or unwanted objects to create something new. We talked about ownership and purpose. Is a bucket still a bucket once it is broken and no longer holds water? Is rubbish still rubbish once we pick it up and use it for a new purpose? We looked at Duchamp’s readymade ‘Fountain’. ‘Is it art?’ I asked them. ‘Of course it is’, one student replied, ‘art can be whatever you want it to be!’ There was a refreshing open-mindedness in the classroom that I certainly did not encounter at GCSE level. Next we asked them to select a number of items from the stockpile that could make a collection. We talked about different kinds of value: monetary value, historical value, sentimental value. Before we had even proposed the idea, the students began making the objects their own and creating new sculptural pieces. Even those who had not been as eager to speak during the discussion became easy and fluid in their thinking as they started to classify, attach and arrange. To end the session, we created ‘one-minute sculptures’, an idea originated by the artist Erwin Vurm which requires wearing an object for a minute, where the act of doing so becomes the sculpture itself. Again, the students fully embraced this new and curious activity without much encouragement.

At Lowick First School, we began by giving each student a small package. I should point out that this term’s theme at the school was ‘Detectives’, and each student had a badge explaining who they were and what special powers they had. Receiving a mysterious object was the perfect case for these wild imaginations. We asked them to talk about what their object might be. We talked about obvious things such as what it looked like or what material it was made of, then we speculated about where it came from or to whom it belonged. Sally and I then asked them to draw a story about the origin of their objects. One student had a small shard of yellow plastic. He concocted a story involving the police chase of a stolen speedboat, the driver of which was not paying attention when he crashed into rocks in shallow water. The fragments of his yellow speedboat drifted out to sea and ended up on the shores of Holy Island. Two students worked together to perform a song about the plastic lure that befriended a fish. The children’s confidence and imagination are a testament to the school’s inclusive and forward-thinking methods.

Although very different schools, they both have something very important in common: the learners are learning and the teachers are teaching. This may seem like an obvious requirement for a school, but it is sadly not the case in most schools across the country. The UK’s national curriculum is defined by testing. Both students and teachers are hugely constricted by the pressure to teach for tests, and any attempt to think creatively or individually about learning is suffocated and quickly left behind. I do not think it an exaggeration to say that, without creativity, there is no learning. Without giving learners the opportunity to be curious, they are simply following orders; and teachers, without the opportunity to engage imaginatively with what they are teaching, are simply delivering orders. Creativity is not necessarily quantifiable and, therefore, largely an inconvenience to our test-obsessed educational system. Testing in itself is not an evil, but it assumes that students progress in a straight line towards a set goal and that through time-based written exams in a silent, sweaty school hall we can understand everything important about the capabilities of the individual. Of course, humans do not move in straight lines, but in random, sprawling and unpredictable lines in all directions, and it is fundamentally wrong that our educational system does not allow for that.

Schools such as the Barbara Priestman Academy and Lowick First School have, in some respects, gone against the rules and, because of this, successfully created a place to learn. It is important that we appreciate this as an achievement, that we recognise the flaws of our national curriculum and realise that a positive educational system is possible.

Text: Ditte Goard, Assistant Arts Learning Facilitator (as part of the Shelter project), 4th year BA (Hons) Fine Art, Newcastle University

Image: David Fudge